So stark and pronounced were Diego Estrada’s troublesome years – extended periods when he could barely muster the motivations to run three miles, when he was so overtrained that his hair started falling out, when he up and quit on two coaches and then quit on himself, when his exacting racing standards led to bouts of crippling doubt – that it can be easy to forget just how good a runner he was and perhaps can be once more.

His return to the form – more like a resurrection, really — that landed him in the 2012 Olympic 10,000 meters still is in the early stages, but flashes of the Estrada who once starred at NAU and showed great promise in the marathon have resurfaced, auguring a late career comeback at age 34.

Judging by his 2024 performances – and for the bluntly pragmatic Estrada, everything always hinges on results – his running renaissance is in bloom after a prolonged dormancy.

In January, seemingly coming back from obscurity, Estrada finished fifth in the Houston Half Marathon in 1:00:49, joking on social media that it only took him nine years to beat his previous personal best. In March at the U.S. 15K Road Championships in Florida, he finished third behind Teshome Mekonen and Hillary Bor. In April, in hot and humid conditions, he ran 1:01:05 for sixth in a half marathon in Berlin.

And last weekend, at the Bloomsday Run (7.4 miles) in Spokane, Wash., he used a strong kick to place second and take home a nice paycheck. This Saturday, he competes in the U.S. 25K Road Championships in Grand Rapids, Mich., with $10,000 going to the winner. It’ll be a stacked field for the 25K, which includes Olympic Trials runnerup Clayton Young, Dark Sky’s Jacob Thomson, Flagstaff’s Biya Simbassa, McKirdy Trained’s Nathan Martin and Mekonen.

But don’t count out Estrada. He has a motivation perhaps the other elites don’t: he needs the prize money. That purse, as well as previous winnings Estrada has earned the past three months, may be modest compared to the appearance fees top marathoners command, but it’s vital to Estrada, who is unsponsored.

As part of his descent into elite running limbo these past few years, he lost his longtime sponsor, Asics, lost his longtime agent, failed to compete in some races because travel costs were prohibitive, failed to find a shoe or apparel company that would even fork over free gear, something pro runners of far less pedigree than Estrada routinely garner.

So, you can perhaps understand why Estrada has thought about calling it quits several times and actually did go on extended hiatuses.

Those days of doubt and self-recrimination appear to be behind him now. No more overtraining. No more overreacting to a single poor race. No more running for the wrong reasons. No more self-destruction.

At long last, Estrada seems happy, content, motivated. And, as the past shows, a happy Estrada is a successful Estrada. But nothing if not brutally blunt and self-aware bordering on self-critical, he knows that some may look at recent history and doubt his staying power and commitment. But he says he leans on his partner of 12 years, Swedish steeplechaser and former NAU runner Caroline Hagardh, his family in his hometown of Salinas, Calif., a new coach and close friends to pull him through.

“I’m very realistic, and I’m my biggest critic,” Estrada said one recent afternoon at Flagstaff’s Kickstand Kafe. “You know, Caroline and I were just talking about it this morning. This, right now, is the best version of me. There are two aspects I think about. One is regret, wondering how I’d been if I’d done things right from the beginning. The other is, I’m optimistic. Because I’d been so down. I’m not at my best. I know I’ll be better in another year. But I feel better now than when I was 21.”

There are several positives showing that Estrada’s cycle of a fit-and-start career is behind him. For one, he now has a Swedish coach, Janne Bengtsson, whose philosophy and training regimen fit with Estrada’s own vision of his career. His bruised body (back, knee, tibia) and psyche (confidence, ego, self-worth) have mended and his promising results thus far in 2024 have fostered renewed optimism.

Only now, more than a decade after logging his first personal bests, does Estrada feel comfortable enough to consider a brighter future for himself in running, not just metaphorically running in place.

He has a solid goal centered on a single focus: Los Angeles, 2028.

“Everything I’m doing now is gearing toward 2028,” he said. “It sounds silly, but I’m already training for 2028. I’ll be 38. It’s going to be in LA. I’m a California guy. This is the one I want.”

Considering that Estrada ran 60:49 at the Houston Half Marathon in January, many speculated that he would have been a late entry into February’s U.S. Olympic Trials, the reasoning being that a healthy and motivated 34-year-old Estrada would have a better chance at claiming an Olympic berth than a 38-year-old Estrada.

Not so, he said. After all, nobody knows Estrada as well as he knows himself.

“Houston was huge,” he said. “That was the validation I needed that we (he and Bengtsson) were doing things right. Only a year with him, and I’ve managed to turn back the clock. I mean, I hadn’t had a really good race since 2015 or ’16.

“I don’t think I would get to those (2028 Marathon) trials if I had run these (2024) trials. What I mean is, I have to take care of myself psychologically and physically. My body was so damaged and so overtrained that, with only one good year of training, it would have been stupid of me to try it at these trials.”

“I just didn’t have the motivation even to go on a run. That went on for six months, and it was around November, and I knew it was over. Between the Olympic Trials to 15K champs I ran in 2022, I didn’t race. I couldn’t stomach the idea of racing again.”

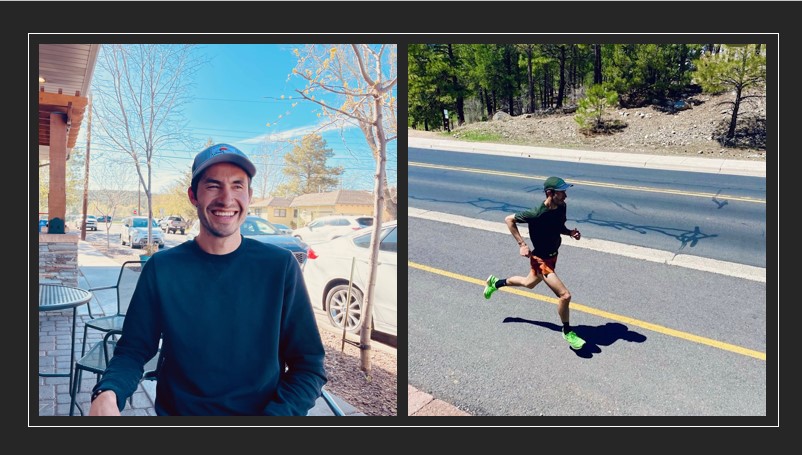

Diego Estrada

Taking the long view is a new stratagem for Estrada, one that seems to be working so far. To appreciate how far he’s come, it’s important to look back at how far he fell.

After what he calls a lackluster performance in the 2012 Olympic 10,000 (21st place), Estrada (a dual citizen of the U.S. and Mexico) and longtime coach Joe Vigil turn their attention to the marathon. His bids to make the U.S. team in 2016 and 2020 ended in DNFs – did not finish – which were near fatal stabs at Estrada’s fragile confidence. There were some glimpses of hope along the way – he ran 2:11:54 at the 20129 Chicago Marathon – but mostly disappointment.

“To elite runners, DNFing is like death,” he said. “Very discouraging.”

He said his nadir hit after the 2020 trials, but intimations of his demise came earlier.

“Around 2019, I knew the signs were there and it was over,” Estrada said. “Nothing I did worked. The Olympic (10K) Trials in 2021, I sort of got it together, but then the bursa on the side of my knee flared up (and he finished 13th in 28:10.78.) After that, I just quit. I didn’t actually quit. I just didn’t have the motivation even to go on a run. That went on for six months, and it was around November, and I knew it was over. Between the Olympic Trials to 15K champs I ran in 2022, I didn’t race. I couldn’t stomach the idea of racing again.”

Did lacking the will to run plunge Estrada into an existential crisis? To wit: If I’m not running, who am I and what is my purpose? After all, he’d been a top runner since his prep days at Alisal High in Salinas, continuing with his standout college career at NAU and his Olympic Games journey.

“No,” he said, shaking his head. “I didn’t like running. I don’t like running. I just like competing.”

Wait, he’s never liked to run?

“I typically don’t enjoy it, no,” he said. “I enjoy the races. OK, I like running the races. I’m very competitive. I hate to lose. And running was just what I was good at in high school. I got hooked on it. When I came to NAU, I was fortunate to have some success, too. Then, after a while, it just disappeared. I was getting 10th or 15th in races, and I just didn’t enjoy it.”

Officially, after 2021, Estrada didn’t retire. Call it something similar to that current workplace phenomenon, quiet quitting. He was just going through the motions, and then not even doing that.

“I wouldn’t admit that I had quit, but I had no passion or drive,” he recalled. “So training for me would be, maybe, run three miles on Monday, do nothing until Thursday, then pretend it’s going to be OK. I built a house for my mom in the fall and winter of 2021 in Salinas. Through that, I wasn’t running. I was working 14 hours a day for my mom for free.

“Then I’d go to Sweden with Caroline (for part of the year) and the atmosphere was, well, we were surrounded by athletes. So it was kind of hard for me to get away from the sport, but I personally didn’t enjoy it and wasn’t training. Mentally, I was just … not there. It’s weird trying to explain it.”

Meanwhile, at the end of 2020, after being sponsored by Asics for seven years, Estrada’s contract wasn’t renewed. That hurt and led to a cascade of other negative feelings.

“The person in charge (at Asics) I knew for seven years didn’t feel the need to pick up the phone and give me a call to tell me,” he said. “You try to be professional about it, but it hurt. That set me back, and my coach (Vigil, now 94), I love him, but he was 92 at the time. My agent wasn’t fighting for me to get any sponsorship. I would’ve settled for gear, anything. There wasn’t any shoe sponsor that would give me free gear. It left a bad taste in my mouth.

“I felt my place in running was done. I was what, 31, 32 at the time? I thought I’d given everything I could give, so I wanted to get into construction and get a job. It wasn’t possible because Caroline is Swedish, and I have to go back and forth. So, getting a full-time job was something I couldn’t do.”

The final blow, Estrada said, was “this dumb idea I had” to get into the elite field for 2022 Boston Marathon, a race he’d never run. Estrada saw it at the time as sort of a capstone to his career, a way to say goodbye to the sport.

“I didn’t care how good I did,” he said. “I wanted to run Boston, then quit. Well, I was already quit in my mind. So, I reached out to Boston (in November, 2021) and I could barely get a bib from them, no accommodations. I thought, ‘You know what, nobody really cares about me as an athlete, so it was all the right signs to just quit.’”

His birthday was a month later, Dec. 19. He was back home in Salinas around his parents and his four sisters and one brother. Estrada said his family is known for its work ethic. They came to Central California from Mexico when Diego was 1 and made a good life for themselves.

“We, as a family, are very blunt,” he said, laughing. “There’s no sugarcoating things. So, around Christmas and my birthday, they were straight up with me. They told me, ‘It’d be nice if you quit because you wanted to quit, not because you’re basically a coward. That fired me up.”

That tough familial love got Estrada training again in 2022. He immediately signed up for the U.S. 15K Road Championship in March and Bloomsday in May.

“They both went really bad,” he said, “but getting my ass kicked fired me up.”

By then, Estrada had cut ties with Vigil, who had been his coach since 2013. He still has high praise for Vigil, but says the coach’s system led to overtraining.

“To me,” he explained, “training was smashing the workout and then next has to be better and better. (Vigil’s) philosophy was specific adaptation, basically, if you can’t do it in practice, you can’t do it on race day. That works well, but if you’re not at the level you’re supposed to be it doesn’t work. You’re digging yourself in a hole. I was fatigued. I lost my hair. It’s come back a lot now. I was balding and my hormones were shot. I was severely overtrained.”

In 2022, starting his comeback, Estrada said he ran into Coach Ryan Hall on the track. They two got to talking, and they decided to work together. It did not go well, according to Estrada.

“Because I’d been overtrained, that one of the reasons I was optimistic that it would work out with Ryan,” he said of Hall, whose own marathon career reportedly was cut short due to overtraining and low testosterone. “Honestly, I saw it as a way, well, I’ll give Ryan a try and if it worked, great, if not my parents and siblings and Caroline would leave me alone.”

Initially, things went well. Estrada finished ninth in the BAA 10K with a solid time, 28:40, and then he followed it up by finishing second in the Wharf to Wharf road race.

Soon, it all came crashing down.

“I started getting sinus infections, and when I get that, that means I’m overtraining,” he said. “That was the common theme with coach Vigil. I’d get a sinus infection every three to six months. In late August and September (2022), I was working out with Ryan in sessions and just hating it. I didn’t enjoy training. It was hard because I didn’t want to be a sore loser, being with Ryan and my teammates. But I just had to leave. I quit (in December). I knew we weren’t clicking. I knew there was an issue there, but I couldn’t pinpoint what it was. I felt like I was rubbing him the wrong way with my attitude. I was there, but I didn’t really feel like I was an athlete.”

Enter Bengtsson, Hogardh’s longtime coach in Sweden. Estrada felt kind of sheepish asking his partner’s coach to coach him because “I felt it’d be twisting his arm to do it.” The two finally talked and started working together Jan. 1, 2023.

“The immediate connection I had, coach-athlete, was great,” Estrada said. “His immediate response was, ‘That would be an honor for me to coach you.’ I felt worthy. I felt somebody wanted to work with me. I told him, ‘Hey, I’m down in the gutters. I’d probably struggle to break 65 in the half right now, but I want to break 60 in the half.

“When I linked up with Ryan, he said, ‘Let’s see how much damage there is and how many layers we’ll have to peel to get you back.’ But with Coach Bengtsson, it was like, ‘I’m in. This is a great challenge. Let’s go.’ It was more like, somebody actually cares and gave a damn about me. That meant a lot.”

Not that there weren’t bumps along the way. Estrada’s first race under Bengtsson was the U.S. 15K Road Championships in March 2023, and he finished a distant 10th.

Afterward, Estrada called Hogardh, distraught.

“I said to her, ‘I don’t want to do this. It sucked,’” Estrada recalled. “She was like, ‘You can’t quit. It’s only two and half months with coach, you have to give him a chance.’ The reason I appreciate Caroline’s feedback is because she’s just like my family. She’s not afraid to tell me to my face if what I’m saying is bullshit.”

He returned to Sweden shortly thereafter and kept training under Bengtsson, whom Estrada said is careful not to overtrain him. He said he actually runs more mileage now (90 per week) than under Vigil or Hall, but much of it with far less intensity, which puts him in a better position to ace double threshold workouts and be fresh for racing.

“It was like I was hiding out in the woods in Sweden winning races there,” he said. “It grew my confidence.”

Then came his breakthrough in January at the Houston Half.

After Saturday’s 25K Championships, Estrada said he plans to run the BAA 10K and Wharf to Wharf again, and then add the Stockholm Half Marathon.

“Right now,” he said with typical candor, “I’m surviving from online coaching and prize money. I’m poor, but I can survive. So, I’m not really desperate right now to get sponsors. I’m having more fun now than when I was sponsored. Of course, I want financial stability like anyone, but the athlete in me is coming out now that I’m in survival mode.”

And maybe, just maybe, he’s liking running more.

Leave a Reply