Normally, I like to run in the morning – the earlier, the better. Not only do you avoid the crowds on Flagstaff’s uber-popular trail system, but you feel as if you accomplished something early even if the rest of the day is sluggishly unproductive.

Today, though, I am advising you traverse the 4.4-mile Priest Draw/Howard Draw loop south of Lake Mary Road in the afternoon, preferably on a sunny day. In fact, a weekend day might be best.

Sure, you’ll run into other trail “users” at that time, but that’s the fun of Priest Draw. It’s a magnet for rock climbers, some of whom are quite entertaining and most of whom don’t mind you gawking at their scaling of a “problem” boulder along the singletrack path.

I remember, about five years ago, my first foray along the trail, which starts off the dirt road, FR 132, about five years ago. I didn’t know, then, that this was a popular climbing spot, so I was a bit taken aback when I spied up ahead a guy who looked as if he had a queen-sized memory-foam mattress strapped across his back.

Told you, I don’t know squat about bouldering, do I?

Of course, what the rock climber was lugging was a crash pad, which, as its name implies, softens the falls when these gravity-defying athletes aren’t able to solve the “problem” and can no longer maintain a firm grip on jagged and serrated limestone boulders.

Priest Draw, and its parallel spot, Howard Draw across the way, are two prime rock-climbing spots in greater Flagstaff. For runners, they also constitute a fun, not-too-taxing 4.4-mile loop through the canyons south of Lake Mary Road, the highlights being the gorgeous geologic giants that protrude along the path — mostly Priest, but a few at Howard, as well.

These limestone monstrosities practically beg to be scaled. I defy you to walk past one of these boulders an arm’s reach from the trail on Priest and not reach out and experience the tactile sensation of the rough, slightly gritty, rock. A few of the bigger boulders have deep indentations, pock marks made through epochs of erosion. They look something akin to giant cheese graters.

Even if you choose to give the boulders a wide berth — some can be a little intimidating just to look at for delicate souls such as me — the 1.8-mile section of Priest is the highlight. Not just because the path is nearly pancake-flat and free of most technical obstacles (roots and rocks), but because you often can catch rock climbers in action not 10 feet away.

They are a wonder to watch.

There’s this one rock about a half-mile south of the trailhead, the top of which sticks out like the stiff bill of a baseball cap. Boulderers climb up it, first vertically, and then horizontally as they go from handhold to handhold nearly upside down, about 15 feet off the ground.

No wonder they use a crash pad. Hell, if I ever mustered the temerity to attempt something so harrowing, I’d use one of those inflatable safety nets that firefighters employ when people are forced to jump from a burning building.

I gawked at a wiry climber successfully solving the “problem” — the term used for the route they choose to take to make it to the top. So intent was the climber on his task, I doubt he ever knew he had an audience.

Farther down the trail, I came upon another climbing party — man, woman and dog — at another limestone shelf not at quite as extreme angle as the earlier boulder. They were friendly types, perched above us on the ledge. They waved and the dog, snoozing on the crash pad, didn’t bark at my pooches pulling on the leash.

Later, I did some deep, scholarly research into this bouldering area on a search engine, and up popped all sorts of reports in bouldering lingo I didn’t quite comprehend. But I loved the names of some of the rocks, so descriptive: Anorexic Roof, Puzzle Box, Floor Pie, Flying Saucer, Tatter Toes Boulder and, ominously, Coffin Roof.

That last name is metaphorical, of course. But there have been some tragic accidents on these rocks. The most noteworthy death came in 1992 when Robert Drysdale, a 22-year-old student and avid boulderer, fell from great heights and perished. A memorial plaque has been affixed to the rock where it happened. The inscription reads, in part: “Robert Henry Drysdale. Found solace on the boulders of Priest and Howard’s Draw. Devoted countless hours developing and discovering challenges to test himself and others. Without his vision this area would not be that which it is today.”

I read the plaque, then took a couple steps back, craned my neck and tried to imagine what it would be like to attempt to scale this vertical beast of a rock, to “solve the problem.” I walked away with a greater appreciation for climber’s courage, not to mention their upper-body strength.

The rock on which Drysdale is remembered is not located along the formal 1.8-mile Priest Draw Trail. Rather, it’s part of a collection of boulders along a path just north of that. Make a right, instead of a left, after crossing the dry wash, walk a few hundred yards, and there it is.

As for the Priest-Howard loop itself, it’s a pleasant jaunt, over before you realize it. For the record, if you park at the Priest Draw trailhead, the loop measured 3.8 miles. But I added a half a mile or so to the run by parking at the pullout on the corner of FR 132 and the Priest Draw entrance. Why? The road leading to the trailhead proper is mega-deep in potholes, mud puddles and other protrusions that will challenge your car’s shocks.

It would be great as a recovery run, or a steady-state day. Priest Draw has a few protruding rocks to deal with, but hardly technical. And once you get onto the singletrack section of Howard Draw, making your way back, it’s quite smooth and you can pick up the pace.

The only slightly tricky part (the only significant elevation gain, too) comes on the 0.7 of a mile connector trail from Priest to Howard.

The Priest Trail ends at another trailhead, a circular parking area at the confluence of several forest roads. To find the connector trail, keep moving straight (south) and, after maybe 30 yards, veer left (north-east) on an unmarked forest road. If you continue slightly right on FR 235A, you’ve made a wrong turn. The (correct) road climbs a bit through some Ponderosa pines, then plunges down into the canyon, Howard Draw.

Rocks dominate that connector section, particularly on the downhill. It’s slow going but completely runnable.

At a “T” intersection, make a left and the road eventually dwindles to singletrack. (There are no directional signs, by the way, nothing that tells you this is Howard Draw Trail.)

From there, it’s even flatter and smoother on Howard for the straight shot back to Priest and the trailhead. There aren’t as many boulders — or boulderers — on the Howard portion, but the wild grasses along the singletrack have grown high in late summer on the draw.

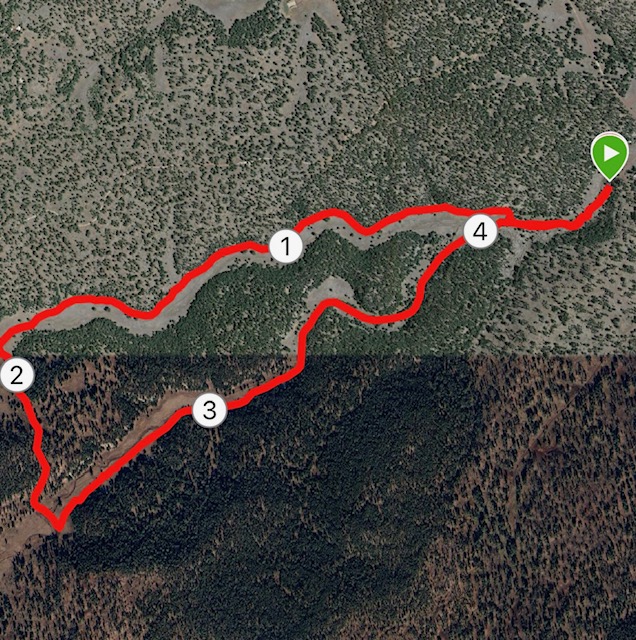

Priest-Howard Draw Loop

Distance: 4.4 miles (if parked on FR 132); 3.8 miles from the trailhead

Driving Directions: Drive southeast out of Flagstaff 6.1 miles on Lake Mary Road. At the “mailboxes,” turn right and follow FR 132 (paved for the first 0.3 of a mile, then dirt) for about 3 miles. Turn right at the sign for Howard/Priest Draw. Drive approximately 0.2 miles to the trailhead parking at the end of the road, or park at the FR 132 intersection and run in.

The Route: Start at the directional sign for Priest Draw Trail (or the intersection). Priest Draw runs for 1.5 miles. At its end, another trailhead, continue up the road for a few hundred yards, then veer left (uphill) on an unmarked forest road (do not continue of FR 235A). After 0.7 of a mile, turn left at a “T” intersection. This is Howard Draw. The road narrows to singletrack. Follow it back to the Priest trailhead.

Elevation gain: 243 feet

Highest elevation: 6,967 feet.

Leave a Reply