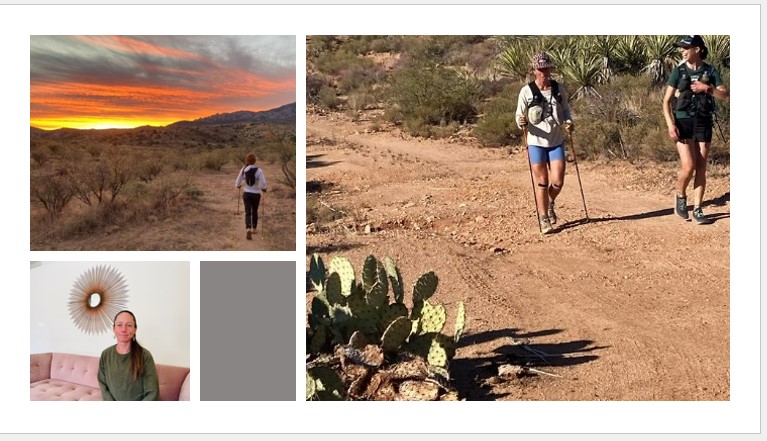

At 4 a.m. on Nov. 21, Flagstaff’s Georgia Porter finished her epic Arizona Trail fastest-known-time quest by successfully setting the record – 16 days, 22 hours 6 minutes – beating the record by some 13 hours.

Exactly a week later, seemingly none the worse for wear, Porter, 36, sat sipping a drink at Foret Flg on the Southside and recounted the many highs and lows she experienced running North-to-South, from the Utah border to the Mexican border.

First, a little background: Porter, who ran for Western Colorado, a Div. II powerhouse, began her running journey on the roads, finishing 28th in the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in Atlanta. Her two sisters also are marathoners, Sarah Crouch, who starred at Western Washington, and Shannon Smith, at St. Martins. (Smith will run the CIM on Dec. 9).

Porter detailed her running odyssey, how she left the time-obsessed world of road running and embraced the ethos of the ultra scene, why she took on the challenge of AZT, and how the journey played out. (The interview has been condensed slightly for clarity and brevity.)

FRN: Let’s briefly start with your background. Different from your sisters, you didn’t run in high school, right?

Porter: No, I was a thrower, and not very good at it.

FRN: A thrower?

Porter: I think my parents told me I had to do something, so that was it. I was definitely the black sheep and rebelled. Everybody else was runners. I was like, I will never run. And then in my mid-20s, I was working as a paramedic and wanted to get in shape. So I trained for a triathlon and had Sarah coach me for it. I did OK in the swim. I did terribly in the bike, I mean, so bad. I got passed by everybody. So, by the time I got to the run, I was angry and like, screw this, and I ran a decent time for somebody who doesn’t train. Sarah said, ‘That’s a really good time. You should consider running.’ She trained me for some (half marathons) and then I went back to school and did the college thing.

FRN: Now that we’ve got you in the running world, how did you wind up in Flag?

Porter: This was a really good way of getting here. Sarah was living in Kentucky, my sister Shannon was living in Washington, and I was living in Colorado. We all decided to go somewhere and train for the trials together (in 2017). Sarah had her eye on either Boulder or Flagstaff. It was kind of her decision to come to Flagstaff. All three of moved here, and it was a sweet time to be living in the same city.

That was the intention – to train for the trials. I was the only one who ended up going, but it was a special time in our lives. Sarah has since moved.

FRN: Why’d you stay?

Porter: I’ve been really nomadic … I thought here would just be, you know, train for the trials and move on. But Flagstaff! I put down roots and I have a community here and bought land here. So, it’s home. I’m not leaving.

FRN: You are a personal trainer, right?

Porter: I was. Now I’m in a program getting certified to guide psilocybin journeys.

FRN: Well, some might say running 817 miles is a psilocybin trip in itself.

Porter: We were joking out there, because I started hallucinating about day eight. And I said, this is the most expensive way I’ve ever hallucinated.

FRN: When did you embrace ultrarunning?

Porter: When I moved here, I did stuff on the roads for five or six years. It was interesting. Over time, I realized I had so much of my identity wrapped up in it. I was constantly just chasing times and losing my love for running. At the trials, I had a really good experience and ran well, so in my mind, the next thing was, OK, get my times down, try to go professional. I just trained myself into the ground. Total burn out. … My last marathon was Chicago in 2022, and I was running 120-mile weeks before that, having massive insomnia. I was so unhappy. I got in the race, started suffering 5K in, and I was out there that something has to change. I don’t love this anymore. I definitely had to experience the, like, death of running on the roads.

FRN: So, you’re saying you had to mourn your road-running career before going to ultra?

Porter: I did. I didn’t know if I wanted to run at all. So I went on this trail run a couple weeks later. Do I want to run? Do I like it? Yeah, I love running on the trails. I think I had this mind of, oh, I’ll run on the roads until I retire at a certain age and then I’ll do trails. I was like, fuck it, I just want to run on the trails now. Why am I not doing the thing I want to do? I haven’t touched much pavement since. I’ll probably never run on the roads again. I still had to work through getting beyond that identity.

FRN: Did you jump right into 50-milers or was it gradual? How did it get to this point?

Porter: Interesting. I never really thought about that. How did it get to the 800-mile point? (Laughs). I started dipping my toes into a 20-miler, a 50K, and it was like the longer the distance got, the more intrigued I got by it. The longer you run, the more crazy high and low experience you go through, and I’m really drawn to that. It’s been three years I’ve been doing this, and it’s just gotten longer and longer. Last year, I did a couple 100 milers and thought, this is the hardest thing ever and the most incredible thing ever. I really enjoy the process you go through in them.

FRN: Isn’t it a totally different mindset doing a 100-miler compared to a road marathon? OK, in a marathon, you go through high and low phases, but not like this.

Porter: I’ve heard it referred to as the distance of truth. Even up to 100K, most people can do that distance. But there’s something about a 100-miler, especially the ones I’ve done in the mountains, where push really comes to shove of why you’re in it and if you’re going to stick it out. You do not know until you’re in it. I don’t know what that is, personality-wise, but I really admire in others putting one foot in front of the other.

“The longer you run, the more crazy high and low experiences you go through, and I’m really drawn to that. It’s been three years I’ve been doing this, and it’s just gotten longer and longer.”

Georgia Porter

FRN: Did you take to ultras right away?

Porter: It’s kind of a war of attrition. I don’t think I’m insanely talented, but I have the resilience to put one foot in front of the other when it really hurts. Ther are some people who maybe have more talent or are faster, but don’t have that (resilience), I may beat them.

FRN: Did you have to get all the road running ideas out of your head, like splits and stuff? Now you’re dealing with technical terrain, vert and all that, did it take you time to adjust?

Porter: It was like a very long, drawn out ego death, I think. (Laughs).

FRN: Yeah, like, you look at your watch on the trail and think, ‘Oh, a 9-minute pace.’

Porter: Absolutely. Or you’re going up a really steep hill and look and it’s a 28-minute mile. You never see that stuff on the roads. It was this long, slow letting go process in races that broke it. The 100s really broke me out of it because at some point, you just don’t care anymore. Even High Lonesome (2023, in Colorado), which I won, I remember being, ‘Hey, if someone passes me right now, great for them. I can do nothing else, I’m just trying to get to the finish.’ It took a lot to break me of that, but it was a beautiful process. After last season, which ended in March, I didn’t use a smart watch at all until I got on the Arizona Trail, because I had to track it. I remembered why we all got into this: because of how it feels. It’s so easy to get sucked into the metrics of it and basing all the value of your experience on that, so I completely let that go. I just went out with a Timex watch and turned into how it actually feels. It’s so nice and took me so long to get there.

FRN: This is a good transition to get into this crazy AZT fastest known time dream of yours. What was the seed of the idea to do this?

Porter: Before running, I came from a backpacking background and I’ve always had a desire to do long trails, like the PCT (Pacific Crest Trail). I’d been on part of the Arizona Trail. But after the 100-milers, I had a deeper understanding that I can do big things. I was just craving adventure, you know. That felt like the biggest possible adventure. Going after the FKT was the framework I built it around, but I really had to let go of that attachment to outcome while I was out there.

At the beginning, I was thinking about the FKT but it was causing me a lot of suffering, if I was feeling off or going slower than anticipated and the days being longer than anticipated. I went through some massive processes out there, having to let my attachment to outcome go. It was really hard. At the end of the day, I can only do what my body can do. My body was teaching me that. The trail was teaching me that. Be here in this moment. You can do what you can do. If an FKT happens, that’s beautiful; if it doesn’t, that’s still really beautiful.

FRN: I don’t know if you’re spiritual at all, but what you’re saying sounds really Zen.

Porter: Yes, and I was struck by the sheer messiness of the process. In my mind, I envisioned that I knew it’d be hard and go through highs and lows, but I thought based on I don’t know what, media or watching other people, that I’d be out there looking like an animal, feeling like an animal. But, in fact, sometimes I was out there at 2 a.m., stumbling on the trails, hallucinating, bawling my eyes out in the depths on my process, and I did not feel bad-ass at all

But really authentically having to let all that stuff go and be present was really challenging. It took days and days and days for me to get there.

FRN: I know I’m getting ahead of the story, and want to delve into the whole journey, but after you finish, did you emerge with a different perspective?

Porter: There were a few massive takeaways. … I’m developing an understanding, as I integrate this, that when we go through things like this, they feel and look really messy while you’re doing it, and that’s totally OK.

Another huge thing for me is, I had the best crew. I know other people say that, but they’re wrong, because I did. My partner Shawn (Roberts), one of my best friends, Meredith (Merkley), my friends Will (Schenk) and Matt (Belus), my friend Kam (Harder) was out there on and off. We became like a little family out there. It was five people and had other people jump in and out (such as Sarah Wilder and Jude Ajaski). But this core group took care of me in such a beautiful way. It was such a practice of receiving (help), which is hard to do. At points, I couldn’t do anything. I was having to get stripped down, wet-wiped, fed, massaged, totally taken care of.

FRN: Sounds like a return to childhood, almost.

Porter: We were joking, either childhood or elderhood. But their energy and love, I never questioned once. I definitely questioned whether I could do it. Their love and support kept me going. I understand what Tara (Dower) is saying about her AT FKT (Appalachian Trail) where it’s ‘We did this. Our team did this.’ I genuinely would’ve not hit the FKT or even finished without them.

For me, it’s always been hard to receive. But seeing how much joy it was bringing them to be part of this adventure. This is something I want to continue in my relationships: to receive and give. (The crew) saw everything, every part of my process and held so much space, and all the beautiful moments, too, the sunsets and animals and laughing and silliness, the crying, the deep despair. They were there for the whole spectrum of it.

FRN: Logistically, how long did it take to get this set up?

Porter: Meredith and I talked about this before the first of the year. I started gathering my crew and the intensive planning was four to six months.

FRN: It’s interesting the time window you chose, and running north-to-south. Why choose that?

Porter: With the Arizona Trail, you either go in the spring or the fall because of weather. In the summer, it’s going to be too hot down south and in the winter, too snowy up north. If you go in the spring, you’re trying to get out of the heat quickly, south to north. If you start north, in the fall, you’re trying to beat the snow and let things cool off in the south. It was kind of a roll of the dice.

FRN: You could’ve been facing an early now, but you didn’t this year.

Porter: I actually timed mine with my (school) program. I had class on a Saturday and left that Monday (Oct. 28). For the most part, we lucked out with weather. The worst of the weather was when it rained in Pine and it was that very heavy, clay-like mud. It was awful, that mud that builds up on your shoes. There was a little snow on the North Rim (of the Grand Canyon) but honestly more on Miller Peak (far south) than anywhere else.

FRN: So you lucked out on weather, except I’m sure it got hot in the desert near the end.

Porter: Down there, you are low some of the time, but you’re also climbing Lemmon, Mica and Miller, so you’re not down at 2,000 feet the whole time.

“I just need to lean into the pain and experience it fully. I felt my relationship to pain change. My pain threshold changed, where I was accepting. The whole rest of the time, I still had that level of pain, but it was in the back of my mind after that. It changed my ability to be with the pain.”

Georgia Porter

FRN: You start off and have an incredible first two days, getting past the Canyon and near Flagstaff. Were you thinking at that point, ‘I got this’? Or were you thinking, ‘I’m going out too fast?’

Porter: The first week we knew would be flatter than down south. Also, you’re feeling better, so you’ll be moving faster. So it’s natural to be averaging more miles, especially south-bound. The first four or five days, things got progressively worse. Like, I definitely (thought), ‘How am I going to do this? This seem impossible.’ My feet were swelling, experiencing a lot of pain in my feet because – well, the biggest mistake I made is, I run my shoes into the ground, so I have 10 pairs of shoes with 500 miles on them, and they are all minimalist shoes. I have really bad nerve damage right now in my feet; they’re numb. I’m sure it’ll be fine, eventually. That foot pain was getting worse and worse by day five, because up to that point, you’re not getting any adaptations yet. You’re just getting more and more tired. The tricky thing was, at night, when I tried to sleep, I was in so much pain that I wasn’t sleeping much.

With the pain, I had one night, the fifth night, things were getting more painful and I was running through the night and had four more hours ahead of me, and my feet were in excruciating pain. I realized in that moment, OK, I can’t keep avoiding this and trying not to feel it. I just need to lean into the pain and experience it fully. I felt my relationship to pain change. My pain threshold changed, where I was accepting. The whole rest of the time, I still had that level of pain, but it was in the back of my mind after that. It changed my ability to be with the pain.

FRN: Let’s talk about eating during the run. Did you have a good stomach and could handle the calories needed?

Porter: I struggled, because I was nauseous in the mornings and then in the evenings, and it was hard to keep stuff down. The great thing is, my body is very efficient at fat-burning, and I don’t think I needed as much calories as somebody more on the carb-burning side. We ate every 45 minutes, a gel or some type of whole food.

FRN: Yeah, I saw some pictures of you on the Instagram account. You ate a lot of wraps?

Porter: (Laughs). I don’t want to eat another tortilla again for a long, long time.

FRN: How much of what you ate was protein?

Porter: I ate a lot, prioritized protein. I took this supplement, Kion, just the essential aminos. I definitely lost some body fat. That’s the fuel it was burning. My pacers kept reminding me to eat and I really resisted it. They stuck with it every 45 minutes, getting 100 to 200 calories down.

FRN: After those tough first five days, did adaptation come? When did you feel better?

Porter: Physically, it started around day six or seven. It was weird. I’d wake up and felt like I hadn’t run at all. That wouldn’t last all day, but I would enjoy the sunrise and my body just got so used to moving that I actually felt better moving than when I stopped to lay down. I was feeling these adaptations. It feels really wild to go through that experience. I knew that was something that happened (in ultra-long distances) but I didn’t want to get my hopes up. It was really cool to feel my body adapt, and I felt a resiliency and steadiness.

“I experienced this physically, mentally and spiritually. All three were different experiences. But physically, there were highs and lows. There were times I felt so fluid and smooth, like I was made to do this. And then there were times I just wanted to die.”

Georgia Porter

FRN: Did you go through periods of dissociation?

Porter: No, I felt present the whole time. I experienced this physically, mentally and spiritually. All three were different experiences. But physically, there were highs and lows. There were times I felt so fluid and smooth, like I was made to do this. And then there were times I just wanted to die.

FRN: During the good times, were you, like, giddy, and during the bad times, despairing?

Porter: Oh, yeah. What I didn’t factor in was so intense the sleep deprivation would be. It was next level. It’s wild when you’re in that place. You can’t hide any of your emotions. It was funny, I came into mile 600 probably on one of my biggest highs. I felt so good. Then I proceeded to go into the deepest low after that.

FRN: Tell me about that last 200 miles.

Porter: We did the last 200 in four days, essentially. The first day, you climb on Lemmon. We had a beautiful time, because I always love climbing, but the descent off Lemmon is step, technical and it was hot. I don’t do well in the heat and on steep technical, even when I am well rested and haven’t run 650 miles. I felt myself moving so much slower. I was getting frustrated. It felt like one of those dreams where you’re trying to reach something, and it keeps getting farther away.

The next day, we did Mica (Mountain) and my Achilles started acting up. It took me a day to realize this, but I literally felt depression. … I didn’t know if it was going to happen. Am I going to crawl to Mexico? But the next day, after Mica, I was able to deal with this with Will, who was pacing me. He just let me cry it out, everything I was feeling. And then I started to come out of it. I felt, this isn’t about the FKT anymore. This is a journey I’m on. I’m in it and will keep doing it. I felt I had to dig into these deeper wells that I had no idea were there.

The last two days, we felt we didn’t want to drag this shit out anymore, so we’re going to go for it.

FRN: Did you know exactly how much you had to cover to get the record?

Porter: They did.

FRN: Did they tell you?

Porter: They did, but I don’t know if I was mentally there to receive it. It was a weird balance of knowing I was almost there but just being present for it. I was on empty, but did a 21-hour day followed by a 22-hour day and I just found these deeper wells. It was in those last two days where I felt I would get this or die trying.

My body held up reasonably well. My mind really went through the deep highs and lows. That was the hardest part. But my spirit? It was strong and steady the entire time. We’re here to do this shit and experience the whole spectrum. So, my middle name is Adventure, and I realized that’s what I was craving out of this experience.

There ‘s so much value in going through the hard and messy parts and feel yourself go through it to see your capacity to handle it and to see the highs that come after. They are so much higher. There’s no feeling like it.

FRN: What were your thoughts at the finish?

Porter: I thought I’d be like, yay, I finished. But I was like, I just want to be done and go to bed. It felt surreal, hard to imagine it was done just like that. It felt infinite when I was out there, so it was hard to grasp when I was done. Part of me was so relieved, because I was ready to stop moving, and part of me was so sad because it’s over.

FRN: As we’re speaking, it’s been a week. How’s the recovery? Did you sleep for days?

Porter: The first four or five nights, it was really challenging because I was still in pain. I’d go to sleep and every second of my dreaming would be me running trail, the entire night. It was very confusing. My body would give me five or six hours of sleep but I was telling it, can we have more? Sleep’s been better the last couple of days. But mentally, I’ve been out of it.

FRN: You sound pretty coherent right now.

Porter: Yesterday, I finally started to feel awake and alert. It was weird to see myself in a mirror. I’m a pretty strong runner and to look at myself, it was a shock. Wow, I’ve lost weight.

FRN: You have a tan, too.

Porter: This ridiculous tan line (on her hand) from my gloves. It’s weird, food-wise. My body is not giving me hunger cues. I think it’s so stuck in fat burning that it’s taken care of itself.

FRN: So, six months from now, the Appalachian Trail, right?

Porter: (Laughs). No, I’ll do PCT before Appalachian.

FRN: Seriously, have you thought ahead?

Porter: In my low moments, I was telling myself, ‘Georgia, do not ever race again.’ I was making myself these deep promises. Do not do Cocodona (250). But the moment I finished, I’m like, ‘OK, Cocodona’s in May…”

FRN: Have you been on Ultrasignup yet.

Porter: I have not. Coming in, I was OK if this was the last thing I did running. I just don’t know (about the future) and I want to be OK with that. But my crew, it wants the next adventure so bad. They were so devastated when it was over. They were living their best lives out there.

If I decided to do something longer, like the PCT, I think I’d need a couple years to remove the trauma from this.

Leave a Reply