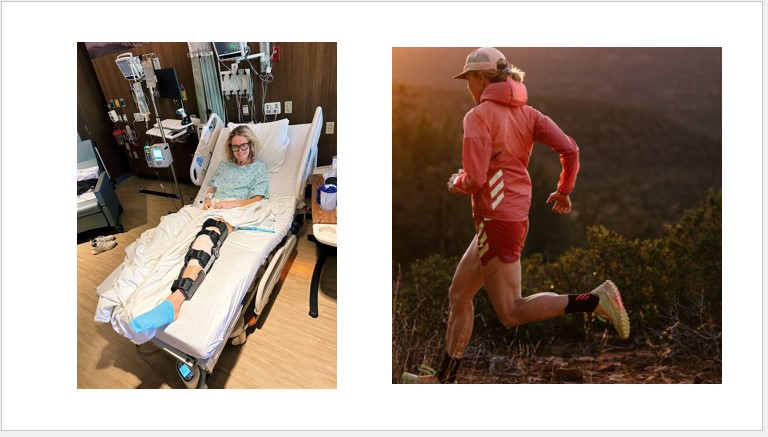

Somewhere along a nondescript trail near the caves at the base of Mount Elden in June of 2023, on a routine hour-long training run, Abby Hall took a step – or, rather, a misstep – that threatened to end her professional ultra running career.

Down she went, her left leg hyperextended, the femur crushing the head of the tibia, the surrounding ligaments shredding like overcooked spaghetti. Surgery followed, a complicated procedure that involved a bone graft for the tibial plateau fracture, reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament, tibiofibular joint reconstruction using a hamstring graft, repair of the medial meniscus and biceps femoris tear and – on top of all that – deep vein thrombosis in the calf.

You don’t have to be an orthopedic specialist to know that Hall was a mess, her left knee swollen beyond recognition, held together surgically by plates and screws. And the damnedest thing was, all this happened on a relatively smooth trail she frequented on a day when she wasn’t even running fast.

“Nothing crazy, nothing technical, nothing remarkable,” Hall recalled, laughing. “In this sport, when you talk about injuries like this, you think of them happening in some remote, crazy place.”

Hall, 34, can laugh upon reflection now, because she has fully recovered after more than a year of rehabilitation and, perhaps, might be better than ever. In late November, she won her first race back on the circuit, the Ultra-Trail Kosciuszko 100K in dominating fashion amid a Australian torrential downpour.

Her return was far from guaranteed, though. The place Hall found herself in after surgery, much to her surprise and chagrin, was in competitive limbo. She had to, literally, learn to walk again on the leg. Forget about competing in UTMB later that summer of ‘23; Hall was staring down months of rehabilitation and an uncertain future.

She had, up to that point, reached the apex of her pro trail running career in 2022 – she placed second in the prestigious UTMB Mont Blanc CCC 100K, won the Transvulcania 100K, won the Innsbruck Alpine 50K and was second at the Transgrancanaria 100K — and she and her main sponsor, Adidas Terrex, had big plans for 2023.

What followed, instead, was months of intense and, frankly, painful physical therapy, which, after the fact, Hall posted on Instagram as sort of a movie montage – more grisly horror film than Rom Com – of her progressing from supermarket-scooter riding, to walker, to crutches, to water running, to anti-gravity treadmill running to, blessedly, tentative steps on the trails.

Adidas stood by her, she said, as did her ultra-running husband, Cordis, and a battery of medical and therapy experts. She did a month-long stint of intensive therapy, eight hours a day, at a clinic in Austria and continued the comeback in Flagstaff, where she and Cordis have called home since 2021.

Not all the rehab was centered on her knee. Hall, who had been running since age 12 and only had one minor injury at age 14, struggled mightily with the mental aspect of having her chosen career threatened.

She enlisted the help of a sports psychologist to, as Hall said, “move forward from the trauma of what happened to me on the trail. Mentally, I was not in a great place. I talked to people who’d been through injuries, and they were so positive, but I cannot say that I was there. It was disheartening, the whole process.”

Part of her work included a form of cognitive exposure therapy, or maybe just an exercise in, well, exorcising traumatic memories.

Yes, the psychologist had Hall go back to the very trail, in the very spot, where she took that fateful step.

“I went back out as soon as I got back from Austria,” she said, smiling at the memory. “We talked through it and put together a little ceremony that I had with myself. I brought some things from my journal that I’d written. I’m very, like, contemplative about my journey and my personal growth in the sport. For me, that stuff is front and center. I’m more focused on that than training data.

“So it was a little letting-go ceremony of this accident and the weight it felt on my life, trying to move forward, making peace with what happened. Not constantly replaying, ‘Oh, if I’d only run a different route that day, if I’d taken an extra day off. If only I’d gotten more sleep the night before.’ “You look back at all the micro decisions that led to it. But I realized I can’t be a perfectionist, and I’ve got to let go of it at some point. Things just happen sometimes. Making peace with that was a big step. I think things like that are important to do in life.”

Demons thus exorcised, Hall kept plugging away physically. There were little victories along the way. She had to use crutches boarding her flight to Austria; a month later, she walked onto the return flight on her own.

She kept improving her mobility and, in November of 2023, started the slow, deliberate rebuild of her ultra training – all with the goal in mind of making a triumphant return to Chamonix, France for the UTMB Mont Blanc 173K race.

Slightly less than nine months after starting to run again, Hall was hellbent on toeing the starting line for UTMB. If the timeline seemed too ambitious, given the severity of Hall’s injury, well, she paid little mind to that. From the moment she was wheeled into the operating room at the prestigious Steadman Clinic in Vail, Colo., for surgery, to the hours of endless rehab in Austria, Hall had UTMB as motivation.

“If I’d only run a different route that day, if I’d taken an extra day off. If only I’d gotten more sleep the night before.’ “You look back at all the micro decisions that led to it. But I realized I can’t be a perfectionist, and I’ve got to let go of it at some point. Things just happen sometimes. Making peace with that was a big step.”

Abby Hall

But journey back, as they say, starts with a single step, and Hall was not so singleminded about UTMB that she didn’t recognize the enormity of actually running again.

“It felt like reuniting with a best friend,” she said about her return to training under the direction of renown coach Jason Koop. “It felt so great. Having gone through so many stages and taking so long, relearning to walk and all that, it made me doubt. Am I going to remember how to do this? But I felt I was back to what I knew best. During the injury was the time of the unknown, but putting one foot in front of the other running? That’s what I know best.”

It took four to six months, Hall said, to build back up to full training volume, which, for an ultrarunner such as Hall, means 100 miles-plus a week.

“Once I started to get back into training,” she added, “I was really surprised to see how smoothly it was coming back. It was amazing to see what the body is capable of and how the body remembers.”

Doubts linger, as doubts annoyingly tend to do.

“A lot of people think of ultra running as being pretty slow, but at the top level, it’s fast,” Hall explained. “And I was doubtful whether I could get fast again. I felt really confident to be able to do the super long stuff again. I felt confident in my ability to endure and grind, but I wasn’t sure whether I’d be back to that place where I’m hitting good workout splits, competing at a top level.”

Koop, she said, brought her along slowly, until …

“We both knew that, when the time came, we were going to try and push it when appropriate,” she said. “UTMB is maybe the toughest mountain race. You have to be ready.”

As sort of a test race last spring, Abby and Cordis jumped into a small race, the Zane Grey Highline Trail Run (27 miles) in late April. Cordis won the men’s title, Abby the women’s.

Things were progressing nicely in her UTMB build – she put in a 130-mile week or two — until …

“Classic story, as old as time, I developed an overuse injury on the other leg,” she said. “The IT band. I was out a few weeks, but even that knocked me down. What’s the metaphor? Like, you’ve climbed the top of a summit, only to realize it was a false summit and there’s one more to go. It felt like that.

“It got me back to what I like to call scrappy mode. Take nothing for granted, nothing’s a given. Keep your head down. Recover well. Do what you need to do to get to the (UTMB) start line at the end of August.”

That, she did.

And, in the Hollywood version of this story, Hall would be triumphant and win (or at least place on the podium) at UTMB and be greeted at the finish line by Cordia, who’d hug and kiss her.

In reality, well, the finish line kiss was there. But things did not go as planned for Hall.

The kiss and hug from her husband was acknowledgement that she had overcome much during her 31 hours on the course, including the luring temptation to drop out, and just finished. Her 31st place was by far Hall’s lowest in her professional career, but UTMB was about more than time and place; it was about completing that promise to herself in her hospital bed.

About 50 miles into the race, at the Courmayeur aid station, Hall was clearly struggling. She sat slumped in a chair, her cap on backward, her face both sweat-soaked and blanched, her right elbow and knee bloodied. She looked near tears.

Cordis bent forward, hands on knees, starting straight into Hall’s eyes when she mulled DNFing.

The exchange has partly been preserved on video, and Hall later posted an excerpt on Instagram. It showed, at once, Hall’s determination and vulnerability and the tight bond between the couple.

When Abby contemplating dropping, Cordis said, “But I want to make sure that you’re not going to regret it in three days, because you don’t get a chance at UTMB every day.” Her brow furrowed, when Cordis said, ‘I’m not going to make the decision for you. If it’s just that you’re having a tough time and you think you can rise out, then I think you should keep going.”

Hall stayed in and finished. Recounting that aid station exchange, Hall explained her conflicting feelings:

“It was the end of a long overnight in the mountains. Everybody comes in in pretty rough shape and in that moment, I was really struggling. I’d dreamed of returning to UTMB for so long but ultimately, I was still dealing with some of the things from the IT band. I came into that aid station not planning on leaving. In that moment, Cordis was able to remind me that this was about something far bigger than fighting for the podium. It was demonstrating to myself that I can be back to the kind of things that I wanted to be back to, that I could push through even if the result wasn’t pretty.

“In ultra running, at an aid station, some people want their partner to be the ultimate cheerleader. For me, Cordis is giving me the hard truth that’s easy to mask during a race. He was there to remind me to remember how much you care about this. Remember how hard you worked to get here. He’s not going to let me off easy.

“In that moment, at Courmayeur – and this is not on that video — I said I wanted to stop (and) at one point he said, ‘OK, you want to stop. All right.’ And he starts to unhook my pack, and I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m not sure.’ Almost by taking it right up to the edge of him going, ‘OK, let’s have them snip off your bracelet and we’ll pull up the car and take off your pack,’ that drew out the reaction of me. Like, no, wait. It’s like where you’re deciding to go to dinner and one person says one thing and then you say, wait, I didn’t realize how much I wanted sushi until you said you wanted pizza. … I pulled back in that moment and said no. He said, ‘See, that’s your decision. You’ve got that last thread of fight in you.’”

UTMB was a learning experience, Hall said, despite her disappointment at her finish.

Finishing, rather than DNFing, turned out to be a psychological boost.

“I came out of it knowing what I needed to work on,” she said. “Coming home from UTMB, I really felt the resolution of a chapter behind me. I’m not sure I would’ve felt that if I hadn’t made it to that finish line. Same thing with that trail ceremony, this helped me let go.

“The one thing the injury really taught me was adherence to daily process. All right, what are the next steps I need to get where I want to be? What are the dials I need to tune now so that I can be back to performing where I want?”

By this October, Hall said she felt fully recovered and ready to race again. She needed at UTMB qualifier because she wanted to race the 2025 UTMB CCC, the 100K at which she twice finished on the podium. Her last chance would be to race the Nov. 29 Ultra-Trail Kosciuszko in the mountains of New South Wales.

About 50K into the race, after descending the highest point in Australia, Hall had a 16-minute lead on the nearest woman. And she felt great, was cruising to an easy victory, until …

“I’m at a road crossing and a guy in an orange vest is waving,” she said. “I think, ‘Uh-oh.’ I’d heard thunder before (on the course). He goes, ‘We’ve been asked to pause the race and we’re going to need you to get off the course.’ He’s there with a van. I’m like, ‘Can I sit in the van?’ He said, ‘No, we’ve got to take you to the last aid station, 5K back.”

The race was halted for two hours, and Hall said she tried to stay positive and sip Cokes and keep stretching. The aid station was filling up with people until it seemed the entire field was waiting there.

Finally, word came that the race would be resumed. Hall thought they would drive her back to the spot where she was pulled off the course. Nope, there would be another mass start from that aid station – meaning she lost that 16-minute lead.

But Hall took off again and not only regained that advantage but built upon it. She won in 10:43:24, more than 27 minutes ahead of second place Juliette Soule of New Zealand.

“It ended up being a 70-mile day for me, but that’s fine,” she said. “When we look at the grand arc of this story, I really think the recent background of my injury helped me be more adaptable on that day. The last several hours, there was buckets of rain, but we only had to run up and down a hill, which is what I like best.”

The result bodes well for 2025 for Hall. She hasn’t mapped out her racing calendar for the year, but she plans to run the Black Canyon 100K in the spring and, of course, CCC in France in August.

For now, she’s back training in Flagstaff, where she says the couple love living. They moved here after several years in Boulder. Abby originally was a graphic designer, first in Los Angeles and then Bou8lder, but became a fulltime pro shortly after signing with Adidas in 2018. Cordis also is an Adidas athlete, but he also manages a tech sales team, working remotely.

“It’s a very peaceful feel here,” she said. “I think the runners here have a really good –- how do I describe it? -– this combination of a strong work ethic and culture of excellence but everyone is really down to earth about it at the same time. It felt like the right fit for us.”

The trails of Flagstaff, she said, never get old.

No, not even that fateful trail near the Pipeline, scene of her step into a world of hurt and ultimate redemption.

Leave a Reply