Running with the Northen Arizona Trail Runners Association crew on its Saturday sojourns is always a good idea. But when the group’s honcho, Neil Weintraub, picks a trail with historic import, then it’s an absolute must-do.

Last weekend, Weintraub and a handful of his intrepid NATRA minions ventured west of Williams on Interstate 40 to partake in the club’s annual Johnson Canyon Tunnel run, a six-miler out and back on a mostly smooth, long dormant railroad grade that leads, well, to Johnson Tunnel, a fascinating Old West relic with a great backstory.

And Weintraub, retired archeologist for the Kaibab National Forest, is just the guy you want imparting the history from way back in 1881, when the railroad first came to Arizona, and that meant carving a huge hole in the hillside about five miles north of where I-40 is today for a singletrack rail line.

We’ll get to the history in a bit. Since the raison d’etre of this website is to feature running, let’s get all the trail stuff out of the way first.

After exiting the freeway at Welch Road and driving on FR 6 for about two miles, you come to a pullout where NATRA begins its run. Why start at that particular spot? Because there’s a sharp downhill just beyond that might test vehicles without high clearance. Those wanting a longer run, say, 10 miles, can park right off the freeway and hoof it from there to the tunnel and back.

How’s the condition of the trail? Exceedingly smooth, except for a few rough spots, including at the start. But once you get on the abandoned railroad grade itself, it’s mostly runnable doubletrack all the way to the tunnel entrance and a little beyond.

Another plus: You won’t see many four-by-fours roaring by and creating dust-bowl conditions, especially along the grade, because some well-placed boulders have blocked access.

A highlight is its remoteness. Except for the NATRA group, there was nary a soul out running, hiking, mountain biking, and there were only a few people dry camping along FR 6.

“You come out here and run the roads, and there’s nobody out here,” said Weintraub, who has done it for years. “I mean, they are less used than the trails in Flagstaff are. This is a wider trail, too. I’ve seen only one other person out running in all the years I’ve come out here.”

It almost – almost – makes you not want to write about the Johnson Tunnel run for that very reason: it might bring out the masses. But what might discourage folks is its location; it’s eight miles west of Williams, getting close to Ash Fork, and then you have to traverse the pinon- and juniper-dotted terrain to get to the starting point.

About the terrain: It may seem, at first, flat, especially compared to the undulating trails in and around Flagstaff. But in that three-mile stretch along the railroad grade, you gain 425 feet of elevation. It’s steady, though not taxing. Plus, you can look forward to a swifter return trip, especially if the wind is at your back.

Which it wasn’t on this day with the NATRA crew. In fact, the wind seemed to devilishly change directions throughout – or maybe it was the runners changing directions.

But, yeah, it can get windy out there. And hot in the summer. There’s not much shade, and you are exposed to the conditions. But in mid-April, the going was quite pleasant.

Now, for that history.

You really want to have Weintraub along to narrate as a sort of ambulatory docent. But if you go solo, here’s a rundown of some of what Weintraub told the group about Johnson Tunnel.

At the start:

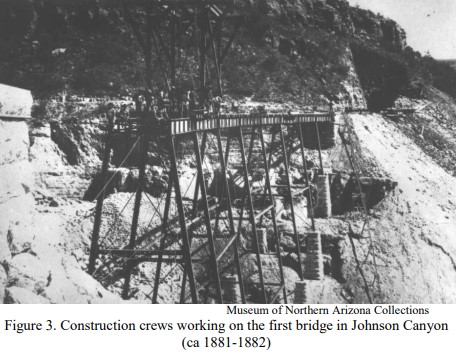

“We’ll go about three miles to the tunnel and the two bridges, built to bring the railroad here,” Weintraub said. “There was a town called Simms (named for James T. Simms, who was awarded the construction contract) that was above the tunnel that supposedly had up to 3,000 people, more than Williams at the time. It was an Old West town, wild, there were shootings and all sorts of crazy things during the six-month period they spent on the tunnel.”

A half-mile into the run, down FR 6, just before making the right turn to follow the old railroad grade, he stopped the group at a large sink hole, called Johnson Crater on some maps, on the west side of the road:

“I had a local who said to me, ‘You know, this is where the spaceships land,’” Weintraub recalled. “I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘Yeah, you government workers. You keep it a secret that Johnson Crater is where the spaceships land.’”

As one NATRA runner observed, the bottom of the crater itself was rocky and tree-lined, and that there were plenty of flatter and more hospitable spots above for extraterrestrial touchdowns.

Along the railroad grade:

“Look for wooden culverts and the remains of signal lights and the names of engineers scraped into the rocks,” he said.

And, finally, at the tunnel, which spans only 328 feet but is pitch-black and seems a lot longer when you’re inside it:

“This (rock) all came from Winslow, Moenkopi sandstone,” Weintraub said. “That ‘McL’ carved into the rock was from McClellan reservoir, built 1911 for the railroad. This originally was called Chinaman Tunnel, and there were supposedly hundreds of Chinese construction workers here. There were some Irish guys who worked, too, who died during the blasting. There were shootings in one of the bars in this settlement called Simms.

“They brought in the steel plates you see inside the tunnel from Delaware. Think about it, that’s a year before the Titanic sunk. Look at the very top, you see the oxidation from the steam. It’s rusted on either side, an orange streak down the middle.”

Weintraub said it took six months to blast out the hillside and build the tunnel, and that the camp was situated above the mesa.

“There was a water source halfway up,” he said. “And see the old telephone poles. There was a lookout shack built on the east portal because during World War II, this was a critical place. They were worried about the Japanese taking out the tunnels and bridges coming from the West.”

Later, on NATRA’s Facebook page, Weintraub posted a link to a paper he wrote about Johnson Tunnel that was presented to the Arizona History Conference in 1993. In that paper, Weintraub details just how perilous life was building the railroad back then.

“The perils of alcoholism, inadequate safety provisions, and a lack of law and order filled a nearby graveyard,” he wrote. “By late 1882, after the railroad became operable through the canyon, people abandoned Simms forever. The camp remains are located above the tunnel. Archaeological materials at Simms include an extensive artifact scatter with broken bottles (a majority of which are broken beer bottles!), milled wood, rusted metal and a few dugouts (probably the remnants of the residential areas).”

In the paper, Weintraub included a newspaper account of an Old West shootout in Simms between two Irish workers, Jas. D. Casey met Wm. H. Ryan. The two were drinking heavily at a Simms saloon, and just outside, Casey shot Ryan twice, killing him. Casey then holed up near the tunnel itself, and a posse was rounded up to arrest him. A standoff ensued, and Casey himself was shot by the posse. The Feb. 3, 1882 edition of the Weekly Arizona Miner paper succinctly wrote: “(Casey) was sent to meet his Maker with the blood of Ryan fresh upon his hands.”

There were lots of other fatalities and shenanigans, as workers had to descend 200 feet down a rocky cliffside to access the tunnel site. A giant rolling boulder killed one worker, for instance.

No such incidents, not even a scraped knee from tripping over a rock, spoiled the NATRA excursion last Saturday.

If you’re interested, Weintraub is hosting a sequel of sorts this Saturday on NATRA’s run. It’ll be in pretty much the same location. The runners will do a six-mile loop on Old Route 66, retracing the steps of the famous 1928 Bunion Derby stage race from Los Angeles to New York. Later In the day, at 2 p.m., Weintraub will give a presentation on the Bunion Derby at the Old Trails Museum’s History Highlights Program at the La Posada Hotel in Winslow. Details here.

JOHNSON CANYON TUNNEL TRAIL

Distance: 6.2 miles (out-and-back course)

Driving Directions: From Flagstaff, take Interstate 40 West eight miles beyond Williams and exit at Welch Road (exit 251). Veer right and take the first dirt road (FR 6) for about two miles (making a left turn at a conjunction at one point). Pull off the road at a small clearing before a steep downhill.

Route: Run north and slightly east on FR 6, immediately downhill and then uphill. After 0.6 of a mile, turn right to continue on FR 6. Eventually, the path turns into the old railroad grade. Continue to the 3.1 mile mark, where you’ll encounter the tunnel. Retrace steps back to the start.

Elevation Gain: 425 feet.

Leave a Reply